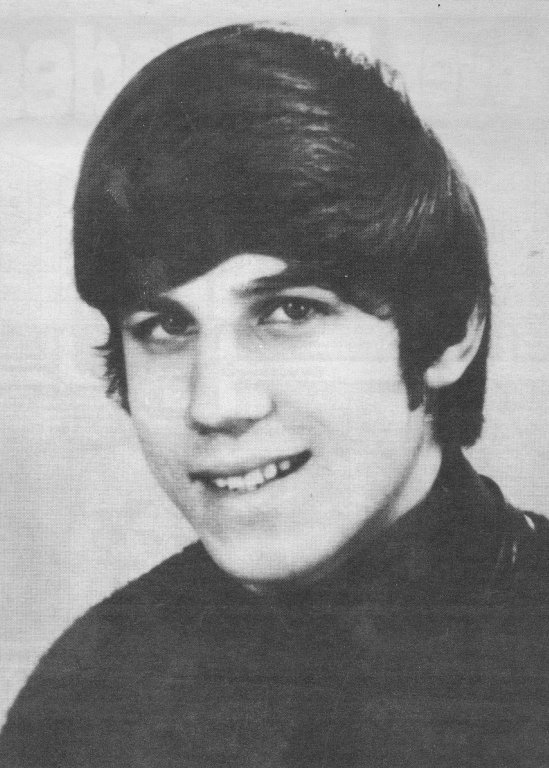

born on April 10, 1949

shot dead on December 16, 1966

near the Teltow Harbor

on the outer ring between Kleinmachnow (Potsdam county district) and Berlin-Zehlendorf

Karl-Heinz Kube prepared for the escape by acquiring two wire cutters from the Konsum department store in Potsdam. These were needed to cut through the wire obstacles. The two young men managed to get passed the first wall, the trip wires and a barbed-wire barrier, and to enter the 12-to-15-meter-wide death strip."Your son participated provocatively in a border breach, was injured and died from his injuries." These words came as a serious blow to Helmut and Martha Kube shortly before the 1966 Christmas celebration. The words were spoken at police headquarters in Kleinmachnow. "I will never forget that sentence," the father wrote in January 1990, a good 23 years later, to Eberhard Diepgen, then mayor of Berlin. [1] They did not learn more about the circumstances of their son Karl-Heinz Kube’s death at that time or at any later date. The father inquired at the mayor’s office in West Berlin whether his son was commemorated with a memorial cross, perhaps bearing the inscription "unknown." A year later, when Helmut Kube wrote yet another letter, he was told to contact the association "Working Group 13th of August." [2] Since the death was not registered in the West, the association advised him to place charges with the police in Berlin against persons unknown. [3] After trying for a year to get more information about his son’s death, Helmut Kube wrote that he was "back to square one" and followed the advice. [4] The subsequent police investigation carried out in March 1993 led to the indictment of the guards believed to have killed his son.

Karl-Heinz Kube, born on April 10, 1949, grew up with four siblings in a town called Ruhlsdorf near Teltow in the south of Berlin. After attending school in Stahnsdorf, in November 1964 he began working in the state-owned Ludwigsfelde industrial plant. He had begun work there as an electric trolley driver in April 1966. [5]

Karl-Heinz Kube was 17 years old in the fall of 1966 when he began making plans to flee to West Berlin with his 18-year-old friend Detlev S. [6] They first considered swimming across the Teltow Canal or ramming through the border with a stolen car. They even thought of escaping with a glider. In the end they agreed to try to escape from the area around Kleinmachnow. Stasi reports show that "Kalle," as he was known to his friends, had some political issues with his surroundings. Stasi documents reveal that he discouraged young people from joining the FDJ, the Communist Party’s youth organization, and that he spoke out against donations for the communist Vietcong in the Vietnam War. [7] The things that he and his friends did like were the very things that his state rejected: western rock music, especially the Beatles, a group which the East German authorities derided at the time as "deadbeats" and subsequently banned. His insubordinate attitude offended the Communist Party leadership at the company where he worked. They even threatened to have him committed to a "youth work yard," a prison-like facility for young people, for political reasons. [8] His friend felt that his career chances in East Germany were ruined: He wanted to be a ship’s cook, but his applications were repeatedly rejected – probably because his father and brother lived in the West. Instead of traveling on the sea, he had to take a training position in the state-run Stahnsdorf guest house.

![Karl-Heinz Kube, shot dead at the Berlin Wall: Wire cutter that he brought with him on his escape [Dec. 16, 1966] Karl-Heinz Kube, shot dead at the Berlin Wall: Wire cutter that he brought with him on his escape [Dec. 16, 1966]](/cache/images/4/178214-3x2-article233.jpg?E876B) On the evening of December 16, 1966 the two teenagers drove with a "Berlin" model scooter from Ruhlsdorf to the border area at Erlenweg in Kleinmachnow, not far from Teltow harbor. [9] They thought that just before the holidays a large number of border soldiers would already be on Christmas leave and the border would not be as heavily guarded – this turned out to be a fateful error. Karl-Heinz Kube prepared for the escape by acquiring two wire cutters from the Konsum department store in Potsdam. These were needed to cut through the wire obstacles. The two young men managed to get passed the first wall, the trip wires and a barbed-wire barrier, and to enter the 12-to-15-meter-wide death strip. At about 9:45 p.m., when they had reached a trench obstacle and were only separated from Berlin by a two-and-a-half-meter-high iron mesh fence, they were seen by border soldiers and came under fire. The two men gave up their escape and sought shelter in a trench that offered them cover and a chance to run back but, as they ran away from one set of guards, they ran into the line of fire of a second group of guards who opened automatic fire on them. Both fugitives ran back and forth in the trench trying to avoid the bullets, but Karl-Heinz Kube was fatally hit by two bullets in the head and chest. Detlev S., uninjured, was arrested and delivered to the Stasi remand prison in Potsdam.

On the evening of December 16, 1966 the two teenagers drove with a "Berlin" model scooter from Ruhlsdorf to the border area at Erlenweg in Kleinmachnow, not far from Teltow harbor. [9] They thought that just before the holidays a large number of border soldiers would already be on Christmas leave and the border would not be as heavily guarded – this turned out to be a fateful error. Karl-Heinz Kube prepared for the escape by acquiring two wire cutters from the Konsum department store in Potsdam. These were needed to cut through the wire obstacles. The two young men managed to get passed the first wall, the trip wires and a barbed-wire barrier, and to enter the 12-to-15-meter-wide death strip. At about 9:45 p.m., when they had reached a trench obstacle and were only separated from Berlin by a two-and-a-half-meter-high iron mesh fence, they were seen by border soldiers and came under fire. The two men gave up their escape and sought shelter in a trench that offered them cover and a chance to run back but, as they ran away from one set of guards, they ran into the line of fire of a second group of guards who opened automatic fire on them. Both fugitives ran back and forth in the trench trying to avoid the bullets, but Karl-Heinz Kube was fatally hit by two bullets in the head and chest. Detlev S., uninjured, was arrested and delivered to the Stasi remand prison in Potsdam.

When he was interrogated by the Stasi in prison, Detlev S. put on record his and Karl-Heinz Kube’s belief "that it was a violation of the principles of humanity that the citizens of East Germany be forbidden by the ‘Wall’ from visiting their relatives in the other part of Germany. I find this kind of measure to be inhumane. I reject it because I feel that it puts limits on my personal freedom." [10] While in prison he wrote a hand-written report on their "arrest," stating that Karl-Heinz Kube was carried "up to the ‘Wall’ that was about 1.5 meters high by two border guards and was thrown over it, and that he got caught with his belongings in the barbed wire and for that reason fell awkwardly. It should also be noted that he had lost a lot of blood and was unconscious. [...] After a while my friend was thrown onto a truck and I was taken by truck to the border watch station. I was accompanied by the words ‘you bastards, someone should punch you in the face.’" [11]

When Detlev S. wrote the report he did not know that Karl-Heinz Kube had been killed; for weeks the Stasi kept this information from him in prison. On March 2, 1967 the Potsdam city district court, presided over by the notorious "people’s judge" Hermann Wohlgethan, charged him with a "collaborative attempt to break through the border in coincidence with the collective offense committed in violation of the decree to protect the state border" and sentenced him to a year and eight months in prison. [12] Karl-Heinz Kube’s scooter was confiscated as a "crime weapon." After he was released from prison, Detlev S. was branded by his escape attempt and discriminated against professionally until East Germany collapsed.

The East German secret police also refrained from telling Karl-Heinz Kube’s parents the details of his death. His father, Helmut Kube, was coerced into signing the following statement at the Kleinmachnow police headquarters on December 21, 1966: "I was informed today by representatives of the Potsdam state prosecutor’s office that my son died during a self-inflicted border breach. I agree to have my son cremated. I was also informed that this would be carried out in the Berlin-Baumschulenweg Crematorium." [13] The parents were not permitted to see their son a final time. The urn containing his ashes was sent to them by mail. The uncertainty of what truly happened to their son, whether he suffered and how he died, preoccupied his mother for the rest of her life. She died in December 1983 at the young age of 54, just before the anniversary of her son’s death. [14]

The four border soldiers, who together fired 40 shots at Karl-Heinz Kube and Detlev S., were awarded either the "Medal for Exemplary Service at the Border" or the "Border Troop Merit of Honor" and invited to a cold buffet. [15] In March 1993, they were charged with committing joint manslaughter and attempted manslaughter. A youth court of the Potsdam district court acquitted them of these charges. The court decision stated that it could not be determined with certainty during the main proceedings which of the accused had fired the fatal shots. [16] There was no indication that in regard to the killing of Karl-Heinz Kube the defendants had "consciously and willingly acted together." The court followed the claim of the former border soldiers that they had not intended to kill and hence had only fired "warning shots" in order to make it appear that they were meeting the demands of the order to shoot. The defendants’ defense plea was "comprehensible" and could "not simply be dismissed as a mere attempt to justify their conduct." [17] The court did not deem it important that, when the deadly shots were fired, Karl-Heinz Kube and Detlev S. had already given up their attempt to flee and were strongly outnumbered. Nor was it considered that the four border soldiers should have been able to arrest the two unarmed, defenseless fugitives without using their weapons. Karl-Heinz Kube’s younger sister commented on the sentence, noting that the acquittal did not remove the defendants’ guilt: "They said they did not intend it and that they did not know about it. But they shot at them! They said that they did not aim. But they hit them! And every one of them knew that if they hit someone, they could kill him. And they did kill." [18]

In the winter of 1966 the youth of Ruhlsdorf wanted to ensure that Karl-Heinz Kube would not be forgotten. But when the East German secret police found out that his friends wanted to hang a picture of Karl-Heinz Kube in the Ruhlsdorf youth clubhouse and attend his funeral as a group, the Stasi went to great efforts to hinder this. [19]

Nonetheless, they could not prevent a teacher at a school conference from asking how she should conduct herself in regard to Karl-Heinz Kube’s death – which meant that all the teachers in the region of Teltow-Stahnsdorf learned that he had been killed while trying to escape. [20]

An inconspicuous wooden cross was placed on the edge of Berlepschstrasse in Berlin-Zehlendorf to commemorate Karl-Heinz Kube, who was killed at the age of 17 merely because he wanted to go from East Germany to West Germany.

Hans-Hermann Hertle

Karl-Heinz Kube, born on April 10, 1949, grew up with four siblings in a town called Ruhlsdorf near Teltow in the south of Berlin. After attending school in Stahnsdorf, in November 1964 he began working in the state-owned Ludwigsfelde industrial plant. He had begun work there as an electric trolley driver in April 1966. [5]

Karl-Heinz Kube was 17 years old in the fall of 1966 when he began making plans to flee to West Berlin with his 18-year-old friend Detlev S. [6] They first considered swimming across the Teltow Canal or ramming through the border with a stolen car. They even thought of escaping with a glider. In the end they agreed to try to escape from the area around Kleinmachnow. Stasi reports show that "Kalle," as he was known to his friends, had some political issues with his surroundings. Stasi documents reveal that he discouraged young people from joining the FDJ, the Communist Party’s youth organization, and that he spoke out against donations for the communist Vietcong in the Vietnam War. [7] The things that he and his friends did like were the very things that his state rejected: western rock music, especially the Beatles, a group which the East German authorities derided at the time as "deadbeats" and subsequently banned. His insubordinate attitude offended the Communist Party leadership at the company where he worked. They even threatened to have him committed to a "youth work yard," a prison-like facility for young people, for political reasons. [8] His friend felt that his career chances in East Germany were ruined: He wanted to be a ship’s cook, but his applications were repeatedly rejected – probably because his father and brother lived in the West. Instead of traveling on the sea, he had to take a training position in the state-run Stahnsdorf guest house.

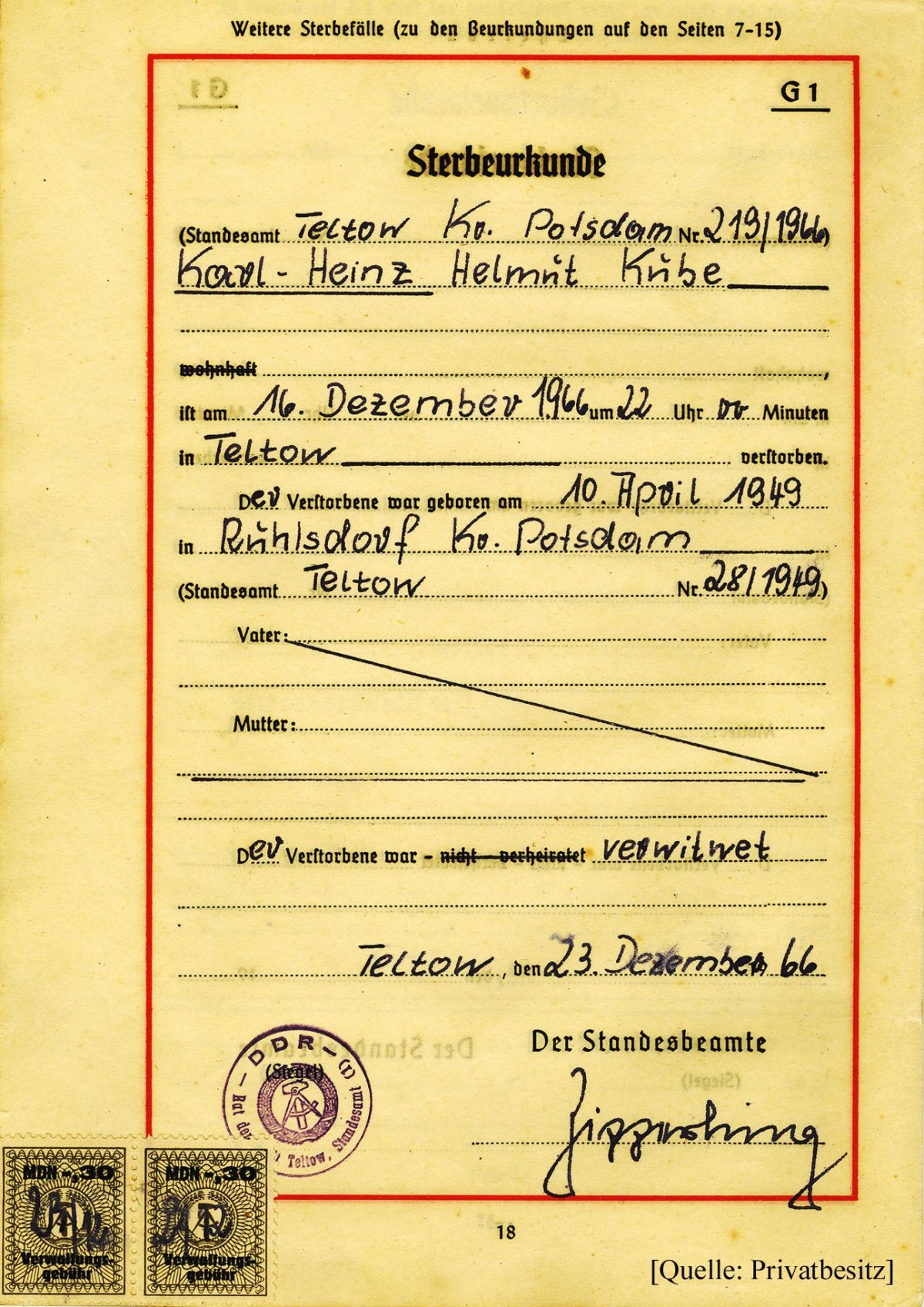

![Karl-Heinz Kube, shot dead at the Berlin Wall: Wire cutter that he brought with him on his escape [Dec. 16, 1966] Karl-Heinz Kube, shot dead at the Berlin Wall: Wire cutter that he brought with him on his escape [Dec. 16, 1966]](/cache/images/4/178214-3x2-article1200.jpg?98CB3)

Karl-Heinz Kube: Wire cutter that he brought with him on his escape [Dec. 16, 1966] (Photo: BStU, Ast. Potsdam, AU 47/467, Bd. 1, Bl. 52)

When he was interrogated by the Stasi in prison, Detlev S. put on record his and Karl-Heinz Kube’s belief "that it was a violation of the principles of humanity that the citizens of East Germany be forbidden by the ‘Wall’ from visiting their relatives in the other part of Germany. I find this kind of measure to be inhumane. I reject it because I feel that it puts limits on my personal freedom." [10] While in prison he wrote a hand-written report on their "arrest," stating that Karl-Heinz Kube was carried "up to the ‘Wall’ that was about 1.5 meters high by two border guards and was thrown over it, and that he got caught with his belongings in the barbed wire and for that reason fell awkwardly. It should also be noted that he had lost a lot of blood and was unconscious. [...] After a while my friend was thrown onto a truck and I was taken by truck to the border watch station. I was accompanied by the words ‘you bastards, someone should punch you in the face.’" [11]

When Detlev S. wrote the report he did not know that Karl-Heinz Kube had been killed; for weeks the Stasi kept this information from him in prison. On March 2, 1967 the Potsdam city district court, presided over by the notorious "people’s judge" Hermann Wohlgethan, charged him with a "collaborative attempt to break through the border in coincidence with the collective offense committed in violation of the decree to protect the state border" and sentenced him to a year and eight months in prison. [12] Karl-Heinz Kube’s scooter was confiscated as a "crime weapon." After he was released from prison, Detlev S. was branded by his escape attempt and discriminated against professionally until East Germany collapsed.

The East German secret police also refrained from telling Karl-Heinz Kube’s parents the details of his death. His father, Helmut Kube, was coerced into signing the following statement at the Kleinmachnow police headquarters on December 21, 1966: "I was informed today by representatives of the Potsdam state prosecutor’s office that my son died during a self-inflicted border breach. I agree to have my son cremated. I was also informed that this would be carried out in the Berlin-Baumschulenweg Crematorium." [13] The parents were not permitted to see their son a final time. The urn containing his ashes was sent to them by mail. The uncertainty of what truly happened to their son, whether he suffered and how he died, preoccupied his mother for the rest of her life. She died in December 1983 at the young age of 54, just before the anniversary of her son’s death. [14]

The four border soldiers, who together fired 40 shots at Karl-Heinz Kube and Detlev S., were awarded either the "Medal for Exemplary Service at the Border" or the "Border Troop Merit of Honor" and invited to a cold buffet. [15] In March 1993, they were charged with committing joint manslaughter and attempted manslaughter. A youth court of the Potsdam district court acquitted them of these charges. The court decision stated that it could not be determined with certainty during the main proceedings which of the accused had fired the fatal shots. [16] There was no indication that in regard to the killing of Karl-Heinz Kube the defendants had "consciously and willingly acted together." The court followed the claim of the former border soldiers that they had not intended to kill and hence had only fired "warning shots" in order to make it appear that they were meeting the demands of the order to shoot. The defendants’ defense plea was "comprehensible" and could "not simply be dismissed as a mere attempt to justify their conduct." [17] The court did not deem it important that, when the deadly shots were fired, Karl-Heinz Kube and Detlev S. had already given up their attempt to flee and were strongly outnumbered. Nor was it considered that the four border soldiers should have been able to arrest the two unarmed, defenseless fugitives without using their weapons. Karl-Heinz Kube’s younger sister commented on the sentence, noting that the acquittal did not remove the defendants’ guilt: "They said they did not intend it and that they did not know about it. But they shot at them! They said that they did not aim. But they hit them! And every one of them knew that if they hit someone, they could kill him. And they did kill." [18]

In the winter of 1966 the youth of Ruhlsdorf wanted to ensure that Karl-Heinz Kube would not be forgotten. But when the East German secret police found out that his friends wanted to hang a picture of Karl-Heinz Kube in the Ruhlsdorf youth clubhouse and attend his funeral as a group, the Stasi went to great efforts to hinder this. [19]

Nonetheless, they could not prevent a teacher at a school conference from asking how she should conduct herself in regard to Karl-Heinz Kube’s death – which meant that all the teachers in the region of Teltow-Stahnsdorf learned that he had been killed while trying to escape. [20]

An inconspicuous wooden cross was placed on the edge of Berlepschstrasse in Berlin-Zehlendorf to commemorate Karl-Heinz Kube, who was killed at the age of 17 merely because he wanted to go from East Germany to West Germany.

Hans-Hermann Hertle

[1]

"Schreiben von Helmut Kube an den Regierenden Bürgermeister von Berlin, Eberhard Diepgen, 28.1.1990," in: StA Neuruppin, Az. 60/1 Js 146/92, Bd. 1, Bl. 3–6, here Bl. 4.

[2]

"Schreiben der CDU-Fraktion des Abgeordnetenhauses von Berlin an Helmut Kube, 2.1.1991," in: StA Neuruppin, Az. 60/1 Js 146/92, Bd. 1, Bl. 7.

[3]

"Schreiben von Helmut Kube an die Arbeitsgemeinschaft 13. August, 6.2.1991," in: StA Neuruppin, Az. 60/1 Js 146/92, Bd. 1, Bl. 8; "Schreiben der Arbeitsgemeinschaft 13. August an Helmut Kube, 13.2.1991," in: Ibid., Bl. 9.

[4]

"Schreiben von Helmut Kube an den Polizeipräsidenten von Berlin, 24.2.1991," in: StA Neuruppin, Az. 60/1 Js 146/92, Bd. 1, Bl. 10–11.

[5]

See "Information des MfS/HA IX/9, 18.12.1966," in: BStU, MfS, HA IX Nr. 12464, Bl. 11 f.

[6]

See "Urteil des Kreisgerichts Potsdam-Stadt in der Strafsache gegen Detlev S., Az. S 48/67 St., 2.3.1967," in: BStU, Ast. Potsdam, AU 477/67, StA 3063, Bd. 2, Bl. 29–34.

[7]

See "Einzel-Information Nr. 977/88 des MfS/ZAIG über einen verhinderten schweren Grenzdurchbruch im Raum Kleinmachnow/Hafen Teltow/Potsdam am 16.12.1966, 19.12.1966," in: BStU, MfS, ZAIG Nr. 1307, Bl. 33–36, here Bl. 35.

[8]

Ibid.

[9]

On the course of events see "Urteil des Bezirksgerichts Potsdam in der Strafsache gegen Werner H., Helmut K., Horst M. und Helmut L., Az. 60/1 Js 146/92, vom 1.9.1993," in: StA Neuruppin, Az. 60/1 Js 146/92, Bd. 2, Bl. 452–455; "Abschlussbericht des Kommandeurs der 2. Grenzbrigade über die Verhinderung eines schweren Grenzdurchbruchs mit Anwendung der Schusswaffe, 17.12.1966," in: BArch, VA-07/6016, Bl. 9–14.

[10]

"Protokoll der Vernehmung von Detlev S. [durch die BVfS Potsdam/Abt. IX], 21.12.1966," in: BStU, Ast. Potsdam, AU 474/67, Bd. 1, Bl. 26–28, here Bl. 28.

[11]

"Handschriftlicher Bericht von Detlev S. über die Behandlung bei seiner Festnahme, Potsdam, den 21.12.1966," in: BStU, Ast. Potsdam, AU 474/67, Bd. 1, Bl. 60.

[12]

"Urteil des Kreisgerichts Potsdam-Stadt in der Strafsache gegen Detlev S., Az. S 48/67 St., 2.3.1967," in: BStU, Ast. Potsdam, AU 477/67, StA 3063, Bd. 2, Bl. 29–34.

[13]

"Statement" forced from Karl-Heinz Kube’s father by the Stasi, 21.12.1966, in: BStU, Ast. Potsdam, AP 1111/76, Bl. 40–41.

[14]

Karola Linow, Soll ihr Schuldbewusstsein die einzige Strafe sein?, in: Märkische Allgemeine Zeitung, 8.9.1993.

[15]

See "Medaille, kaltes Buffett – und kein Wort drüber!," in: Märkische Allgemeine Zeitung, 20.8.1993.

[16]

"Urteil des Bezirksgerichts Potsdam in der Strafsache gegen Werner H., Helmut K., Horst M. und Helmut L., Az. 60/1 Js 146/92, vom 1.9.1993," in: StA Neuruppin, Az. 60/1 Js 146/92, Bd. 2, Bl. 455.

[17]

Ibid., Bl. 458.

[18]

Karola Linow, Soll ihr Schuldbewusstsein die einzige Strafe sein?, in: Märkische Allgemeine Zeitung, 8.9.1993.

[19]

"Bericht des MfS/KD Potsdam über Diskussionen in Ruhlsdorf zum Ableben des Grenzverletzers Kube, Karl-Heinz, Potsdam, 6.1.1967," in: BStU, Ast. Potsdam, AU 474/67, Bd. 1, Bl. 67–69.

[20]

Ibid., Bl. 69.